I am reminded that I am a doctor of economics, and yet I haven’t written much about economics lately. Now seems like a pretty good time.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) released it’s second quarter GDP numbers a week or so back, and GDP shrunk by 0.9% in the second quarter of 2022, after shrinking 1.6% in the first quarter. This is an “advance” number, and will probably be adjusted a half dozen times over, but there it is: a smallish negative growth number.

Now, the textbook definition of a recession is something along the lines of “economists disagree, but generally two consecutive periods of negative GDP growth is accepted.” I didn’t misplace the quotation marks in that paraphrasing. The definition always comes with a caveat, in part because you could find an economist to disagree about what color the sky is if you looked hard enough, but also because, well, what the hell’s a recession?

Most people would be hard pressed to define a recession without referring to the metrics used to recognize that we are in one, along the lines of saying “A house is the thing you are in when you are inside a house.” Generally, though, a recession is when the economy is doing poorly, not growing the way it should be.

Which again… how do we know how much it should be growing?

Well, it shouldn’t ever be shrinking, damnit. We generally agree on that.

To further refine such highfalutin notions, we might ask questions like:

Are people producing and purchasing more goods than they were before?

Is there more or less trade in general happening?

Can people find employment if they want it?

Can employers find people to work for them if they want them?

Are people accumulating wealth, or debt?

Is it easier or harder for people to buy the things they need compared to some earlier period?

Are businesses closing or opening more, on net?

Is worker productivity going up or down?

Note that almost all those are relative measures. It is probably easier for people to buy the necessities in 2022 than it was in 1822, but that doesn’t mean that 1822 was a recession because the economy then was very different than the economy now. It should be a lot easier to get by now than then. So the real question is whether the economy is doing better now than it was over the past few years, and how close it is performing to its potential.

How do we know the potential of the economy relative to what it is doing?

Let’s be good macroeconomists and pretend that last question never got asked1.

Anyway, those are a lot of questions! But that’s what economists are for, right? They should know the answer to whether we are in a recession and how well the economy is doing, right?

Remember how I said you can find economists to disagree about anything2?

So… let’s just look at the numbers behind some of those questions above, because it makes me a bit uncomfortable when Arnold Kling and Paul Krugman are agreeing that the GDP numbers don’t matter and we aren’t in a recession. Something doesn’t make sense to me there.

Are people producing and purchasing more goods than they were before?

Well, according to the BEA numbers, no, not really, purchasing is down. The chart there is not exactly user friendly, but on the purchasing side incomes have not grown much, about 0.6%3 a month, but prices have been increasing faster, driving actual disposable income down. In other words, the prices for goods and services have been increasing faster than the price of labor, so goods/services are relatively more expensive than labor, even though both are increasing. Remember that bit, its important for later.

We have seen that production is down already; that’s what GDP purports to measure, albeit badly. We also have a fair sense it has been a problem considering the widely reported issues with empty grocery shelves, long delays on restocks and products, etc. I work in supply chain so this is perhaps a bit more salient to me, or I am a bit more biased towards its importance, but there just isn’t as much stuff out there. Businesses are not worried about generating too much inventory so much as they are worried about fulfilling customer demand at all.

So less is bought and there is less to buy. Not great.

Is there more or less trade in general happening?

Again, GDP is supposed to be measuring this, so “less” would seem to be the right answer here. You can’t buy goods that are not available, and it does seem like there is less to go around. Probably because we closed down half the world for a year or two.

One can argue as Kling does that -0.9% is less than the margin of error for the measurement, but then again GDP usually grows at approximately 2% yearly these days. Is it enough to say “it is definitely negative”, or “maybe zero”? I mean, 0.9% being within the margin of error implies that half our yearly GDP growth estimate is within the margin of error. That’s a bit shocking to me if true. In any case, growth being zero or negative seems pretty bad, even if you can’t tell which it is. It is supposed to be positive, noticeably so.

Can people find employment if they want it?

This one might be “yes”, which is the strange part, and why Kling thinks we are not in a recession. The Bureau of Labor Statistics has been reporting increases in net jobs (jobs created - jobs lost) for the past few years. Granted, that was after losing 20,000,000 jobs all at once in April of 2020, but a half million a month over 24 months is at least getting things back to what they were4.

The unemployment numbers follow this, with unemployment going down just a touch, although labor force participation went down over the past few months. That’s not ideal, and makes the unemployment numbers lower than they really are.

(Why? People are only defined as unemployed if they are looking for work; if they give up looking for a job they stop counting as in the labor market. So, if a person can’t find a job and says they are looking, unemployment goes up; if that exact same person stops trying and becomes a heroine addict, unemployment goes down. Unemployment is not the best signal by itself.)

Still, steadily adding jobs is a good thing. How good it is depends on the types of jobs, what they are doing, the productivity of the jobs5, etc. Still, if jobs were down it would be really hard to argue against recession; jobs being up a bit muddies the water a bit.

Can employers find people to work for them if they want them?

This damn question… no one seems to track this. Admittedly, it is hard to track without surveys. People who can’t find a job but want one at least apply for unemployment checks. Businesses who want to hire people but can’t is sort of nebulous, and one is tempted to say “If you wanted to hire more people, why not just raise the pay for the job till you can?” Of course it isn’t that easy, because there is a difference between “I would totally hire three more line workers at the going wage rate if I could” and “I would totally hire three more line workers at twice the going wage rate if I could, and raise the wages of all my other workers accordingly.” A rather big difference, in fact.

One wouldn’t tell someone in the middle of a famine “Well, if you were really hungry you would just pay more for food.” The problem isn’t that there is lots of food but the price is higher than they want to pay. The problem is that there is not enough food, and that is why the price is high. The situation needs fixed, and you fix it by producing more food6. If something is preventing more food from being produced, prices going up does not indicate a fat and happy future ahead.

Unless you are really into cannibalism, and always looking for the low fat menu option.

What was I talking about again? Oh right… not cannibalism for the health conscious, but rather employment markets.

The easiest measure of the ease of filling jobs is labor force participation, again. That doesn’t tell you what sorts of workers you can find, but it at least gives you an idea of how many possible workers are actually working, or at least looking to work. If you really want to hire a dental hygienist but only brick layers are looking for work, I can’t quite help you there.

It is worth noting that if there was a really healthy economy and a shortage of workers, one would expect wages to go up quite a bit, faster than the rate of inflation. That would imply the relative value of labor was going up compared to non-labor inputs, and we would expect this to lure people back into the labor force. That doesn’t seem to be happening here, either.

So, alas the answer here seems to be that it is a little harder to find people to fill job spots, based on labor force participation and surveys, but it isn’t really clear one way or the other. Wages are growing more slowly than prices of goods and services, which suggests labor isn’t the constraint.

The best we can do here is shrug and say “Well, it doesn’t look good… but I don’t know that it looks really bad, either7.”

Are people accumulating wealth, or debt?

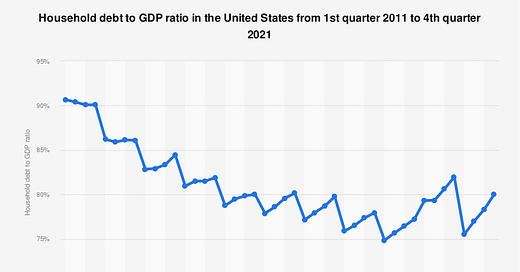

This is a tough one to answer now, as data only seems to go till 2021. Statistica has some numbers on US private debt as a percentage of GDP which show debt steadily decreasing till 2020, exploding a bit, then dropping down to 2019 levels in Q1 2021, then steadily going back up towards the 2020 high by Q3 2021.

What’s that mean for now? No idea… 2022 household debt could be anywhere, although casual empirics suggest it is going up. See above regarding the drop in disposable income due to price increases outstripping income increases.

As for the federal government debt, according to the St Louis Fed.’s report US debt to GDP went up in the first quarter of 2022 after declining since 2020. Of course there were those big spikes in spending in Q2 of 2020 and Q1 of 2021, but other than that spending has been following its increasing trendline pretty consistently8.

So household debt change is a little up in the air, and your guess is as good as mine. National debt is tooling along at pretty close to its natural rate, only getting that uptick in Q1 of 2022 in the graph because it is debt to GDP, and GDP went down. Still, increasing government debt and a widening CPI:Wages spread bodes poorly for the economy. It isn’t booming, that’s for sure.

Is it easier or harder for people to buy the things they need compared to some earlier period?

Yes, harder. Very much so. We’ve seen that in the CPI to wages numbers. We’ve seen it in empty store shelves. We’ve seen it in month long delays for some goods. I’ve seen it in absolutely ridiculous difficulties in getting raw materials and intermediate goods for manufacturing. Overall supply of goods has very obviously contracted.

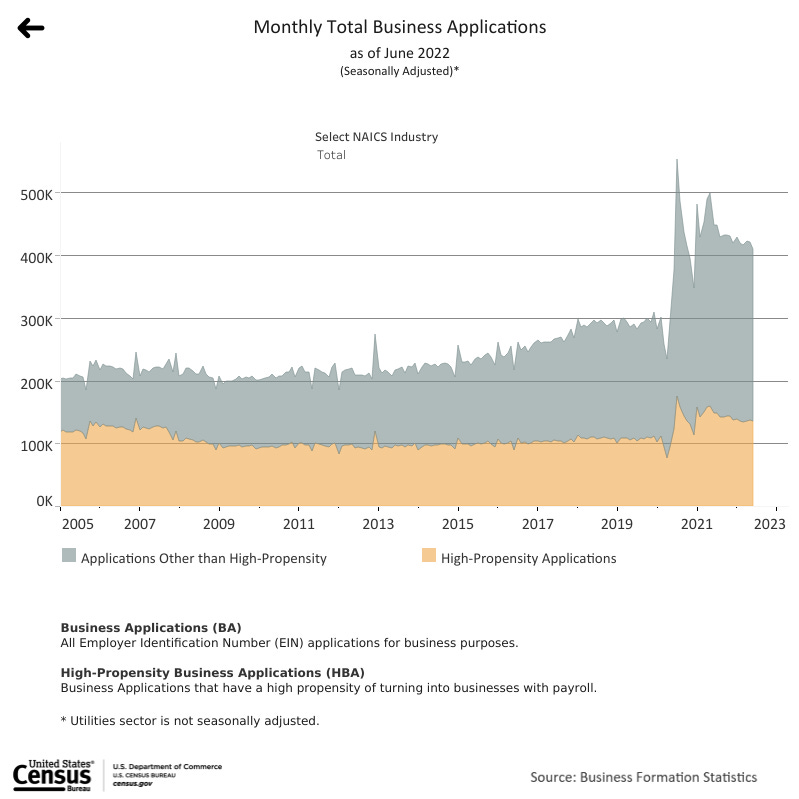

Are businesses closing or opening more, on net?

This one is a little tricky, too. The BEA does not record this, but the Census Bureau does keep track of the applications for tax ids by month. So that’s a bit handy in that it tells you how many people are looking to start a business. (Their latest report is here.)

That’s not a great sign… applications for tax ids have been dropping since the peak of 2021, although they are up since 2019. The question is whether that post COVID peak is due to lots of booming new business activity, or just replacement activity after a whole mess of businesses went under in 2020. In other words, are we adding businesses on net since 2020, or just slowly filling in the great smoking craters left in the economy after the lockdowns nuked it?

Sadly, the Census Bureau fails us here, not having Establishment Birth and Death statistics past 2019. Strangely, no one seems to know how many businesses there are in the US lately. We have numbers on applications to be a business, but no actual numbers on how many businesses there are, or how many have started or closed nationally for the last few years.

Left with just casual empirics again, there seem to be a whole lot of empty businesses downtown here since we moved in ~15 months ago, and I see lots of closed restaurants all over the place. I’ve been traveling for work a lot lately and it seems pretty wide spread and not just “SE PA is unusually bad lately.” My guess, therefore, is that the spike in new tax id applications is due to new companies filling in the holes left by other businesses getting wrecked by the lockdowns and other COVID issues.

Of course this still leaves the question of how big these companies are. If one company employing 500 goes boom and gets replaced by 5 companies hiring 100 people you have roughly the same economy as you had before, despite a 5:1 ratio of establishment births:deaths. In this case, however, I suspect it was mostly the smaller businesses that took things the worst during the lockdowns, not the larger ones, but still worth keeping in mind.

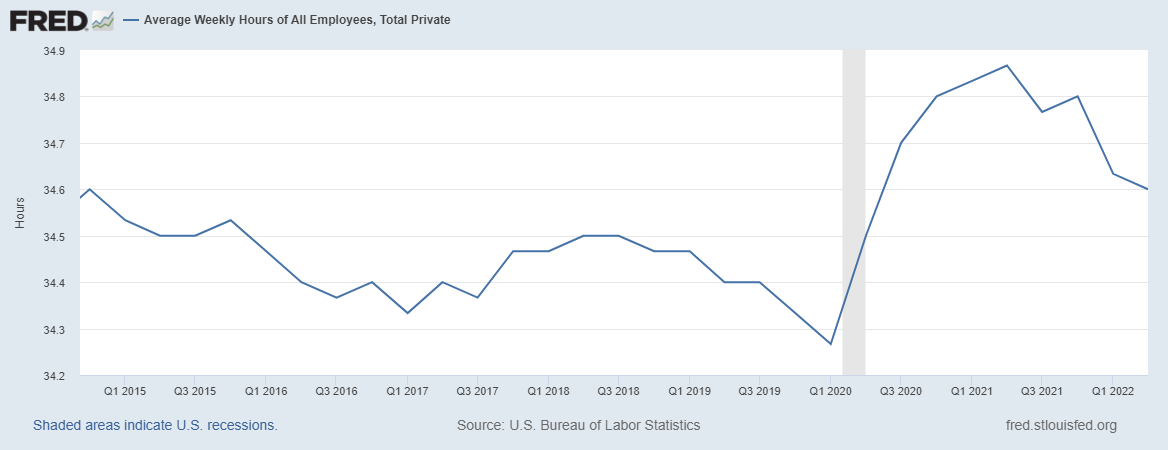

Is worker productivity going up or down?

This one is, again, kind of tautological. More workers in jobs working more hours combined with lower GDP means productivity has dropped, by definition.

Effectively, productivity growth is less than zero most of the time, then there are some big spikes for some reason, then it goes back to being close to zero or less. Fantastic.

At least in this case we can see what we pretty much already know: productivity starts dropping after the middle of 2021, and stays negative into 2022.

Did we know that, though? I mean, we knew jobs numbers were growing, but did hours worked go up during this time?

Whoops… they did not. In fact, average weekly hours in the private sector has been dropping quite a bit since the last peak. Those new jobs have been mostly part time, in other words, dropping the weekly average.

That solves one of the conundrums we had, how employment numbers could be going up while GDP was dropping: more jobs, but not full time jobs, just part time9. The net job creation number was misleading, because it was mixing up the types of jobs, showing more jobs and hiding that people are getting fewer hours.

“So, are we in a recession or not, doc?”

Me, I would say yes.

More importantly, because I am an economist and like to argue and be correct, Arnold Kling should say yes, too. More jobs is easy, just replace full time workers with part time workers. If your argument is that job numbers are more telling than GDP, ok, but look at what the jobs are. Someone who has to work two part time jobs because they can’t find one full time job looks really good in those job creation numbers, but probably is not where they want to be10, nor contributing to specialization and trade as much as they could be.

Does a recession matter? I would also say yes. I think it especially matters leading into a mid term election where the incumbent party looks like they are going to get slaughtered because voters are very concerned about the economy and the politicians want to talk about anything else other than how they caused it. They would love to be able to deny there is anything wrong at all.

Does it seem like the economy is doing well to you?

Yea… you didn’t need me to tell you that. But I am glad you read to the end, just the same.

I have a rather dim view of that branch of the discipline. Mea culpa.

Admittedly, using the internet to find economists arguing a recession has started is a little harder, considering the main news sources are rolling with the administration’s claims to the contrary, but here we are.

Not 6%, 0.6%, or 6 in 1000.

We are still on net down ~800K jobs since the crash of March 2020, however.

In the business we call this “foreshadowing.”

I have enough disapproving thoughts on economists’ divorce from the realities of markets and businesses due to their torrid affairs with white board models to fill its own essay or seven, so I won’t go into it much more here.

…said the Jesuit to the widow.

Eyeballing it based on the Rule of 70, government expenditure grows at about 4.67% a year. It’d be great if GDP was anywhere near to that, wouldn’t it?

Anyone else find it strange that we know how many hours people work on average in Q1 2022 but we don’t know how many businesses there are?

I would also point out that teen agers getting part time summer jobs add to the jobs numbers too, but let’s not over do it.

It's telling that instead of explaining what their plan is to fix the economy, the establishment response is to gaslight, quibble over definitions, and redefine words. Par for the course for the symbol manipulators.

"I have enough disapproving thoughts on economists’ divorce from the realities of markets and businesses due to their torrid affairs with white board models to fill its own essay or seven, so I won’t go into it much more here."

It's even better when the white board model output is reported as "research showing X" or "study proving X" or "evidence for X"