You know it has been a rough month when your next best idea for an essay is a few anecdotes about accounting practice…

But these are good ones! The topic also relates indirectly to a post Arnold Kling put up touching on the troubles with mathematical modeling in economics. Kling’s overall point is that mathematical models help avoid internally consistent claims by forcing a little clarity, but are just as vague as verbal models when applied to the real world. Defining the terms and tracking them in the real world is tough.

It is all well and good to say “perfectly competitive firms will always charge the same price, equal to the minimum of average costs”, but perfectly competitive firms don’t exist in reality, and even if they might you would have to test it by checking that they are all charging the same price which also equals their minimum average cost. The trouble with that, or at least one of the troubles, is that costing is hard.

Some time ago, around a decade now, I worked for a chemical company as a master production scheduler. I made up the weekly and monthly production schedules for the plant out into the future based on orders and forecast, and the detailed schedulers took that week to week and tried to make it actually work so the guys could make it.

There were two main difficulties to overcome. The primary one was that the plant made many different products on the same resources, which were basically giant witches’ cauldrons on legs1. Stuff got poured in, mixed about, heated up, and allowed to soak, not necessarily in that order, and then were pumped out into some tanker or another before the cauldron was washed and a new product was made. Not having dedicated lines or resources thus made every production decision a tradeoff. Deciding what to make was as important as how much.

Many sales and marketing guys deserved to be choked out after answering “Both” when asked “We can’t make both these new orders next week; which one do you want me to make?”

The other problem is related to the needing to get choked to death issue: profitability on a single product was really tough to figure out. The issue is that you could look at the costs of a good being just a question of the cost of the materials to make it, plus some fixed overhead representing plant and administrative costs. That’s the basic average costs in the economic model, which is based on the assumption that you have the plant and workers there whether they do anything or not, so just divide it up. The way to minimize average cost is to make and sell2 more stuff (to spread out overhead) with cheaper inputs (whether materials or total wages). This is roughly Cost Based Accounting.

But it got worse in a mixed resource plant like ours. Remember those tradeoffs about what to make? Well, when the plant is at or near full capacity, every material you make is also a bunch of different materials you are not making. In economics we call that the opportunity cost. So if I decide to make foaming agent A and not emulsifier B, the cost of A isn’t just the average costs of the wages and materials, but also difference in profit from sale of A and B. If I am doing my job right (and sales and marketing will just bloody tell me how) I want to be making the batch that has the higher profitability.

(Of course, that causes more problems in terms of trading off profitability now on a single spot batch vs long term contract or partner agreement with another company, yadda yadda. Not my circus, not my sales monkeys.)

This is the essence of Activity Based Costing. The idea here is that, actually, you don’t have to pay workers whether they are doing anything or not, because they are hourly and get overtime, so you want to be making decisions like “is it worth it paying ten guys overtime to get this order out tomorrow instead of next week?” You also have to make choices about what those guys do while they are working. If Dave and Sara are needed to make product B, but only Dave is needed to make product X, then if I make X Sara can make something else, and B is thus costing me both X and whatever else Sara could do. Likewise with machines and other capital equipment.

Hell, why am I even running a chemical company? We could be making soup instead!

Or, at the very least, it would be nice to know what product to make next week since these new orders are mutually exclusive. Just because those poo flingers down the hall can’t give me a straight answer on this, well, someone knows, right?

Well, let me tell you about some emails I got one week.

It was a cold NE PA day and an email came through from marketing’s Director of Sales or some such. The message was simple: don’t accept any more orders from Customer A for tolled Science Stew product. It is terribly unprofitable for us, and we are just going to have to withdraw from that business. Great, think I, that will ease up things at the end of the month. No more Science Stew for you!

The next morning, also cold and in NE PA, I get an email from the Sales Director. The message was also simple: please expedite orders for Customer A’s Science Stew, and oh, if a sales rep could solicit some more orders from them that’d be great; it is our most profitable product after all! Hooray for Science Stew!

Needless to say, there was much grumbling and cursing among the supply chain and operations guys. Replies went out to the Director of Sales Director, kindly asking them to make up their goddamned minds so we can make things, and oh, do something with the rail cars full of poison sitting in the yard.

Eventually inertia won and we just kept making the stuff like we had before, no more, no less. Neither I nor my boss ever heard back definitively from Sales Director of Sales.

So, what happened? Well, this product was a tolling product. That means that the customer sent us all the raw materials, those rail cars of poisonous goo, and we got paid for cooking them up in our witch’s cauldron for a week or two and then sending it back. We had been doing this for years, yet we could not apparently agree on how much it cost.

From a Cost Accounting perspective, it was a huge win. They were providing the material and paying as though we were, just to use our cauldrons and witches. It was like a bar going BYOB but still charging you 5$ a bottle to drink it at their tables.

From an Activity Based Accounting perspective, it was a huge loser, because it took up about a half month’s worth of cauldron time to make, whereas most products could be turned around in a day or two. We could make and sell 32,000 gallons of Science Stew in those two weeks or 320,000 gallons of damned near anything else, and the profitability of Science Stew was not 10x all that other stuff.

But Science Stew hardly takes any man hours! You just get it started and then the guys can go do other stuff.

We have plenty of guys! What we don’t have is enough cauldrons!

And so it went back and forth. Talking with the detailed plant schedulers, most of whom had been there since my dad was in short pants, it turns out this debate happened about every 2-3 years. If the plant wasn’t too busy Science Stew was a great way to make money with a spare cauldron. If the plant was busy, it was a waste of a tight resource. Sooner or later when the plant was near capacity for a few months in a row, someone in sales and marketing would notice and raise this fuss. They would argue back and forth, but the real answer was “Sometimes it is this way, sometimes it is that way,” and eventually they would go back to just making it when they had time.

Back when I was teaching my office was down the hall from a really excellent accounting professor. When I say “really excellent” it is because she actually could make students excited about accounting.

ACCOUNTING.

Anyway, one day I asked her about this story, and what she thought about cost based vs activity based, and what good companies did.

“Oh” she replied, “everyone just does Cost based accounting. Activity based is far too complicated and everyone gets different answers to the same question.”

“Oh? But isn’t activity based costing far more accurate and useful in figuring out what the company should actually do? I mean, how do you know what to make, or what to charge for goods?”

“It is more accurate but you keep getting different numbers? Accountants need the numbers to always be the same, no matter who does them. If you can’t agree on how to do Activity based so that happens, there is no point. As to pricing, you just estimate the Cost based number and slap on 10-15% mark up, then work from there, usually. Even with Cost accounting your numbers change year to year, month to month, anyway, so it doesn’t really make sense to worry about it too much. Especially if you are selling businesses that all have individually negotiated rates. You are just aiming for a number you have to exceed to be profitable. You have to choose what to make based on those estimates.”

At this point there was a definite “Aren’t you an economist? Why don’t you know this?” flavor to her responses, so I thanked her and let it go3.

All of this to say that pretty much nothing in real live businesses happens with mathematical precision. How much does something cost? We don’t exactly know, and our success or failure depends largely on how close we can nail it down and how well we can make decisions based on extremely incomplete information. As a result, we have almost no ability to apply mathematical economics models to the real world, much less test them, because the not only are the variables in the model difficult to map 1:1 to real world values, but we often don’t actually know the real world values even when we can.

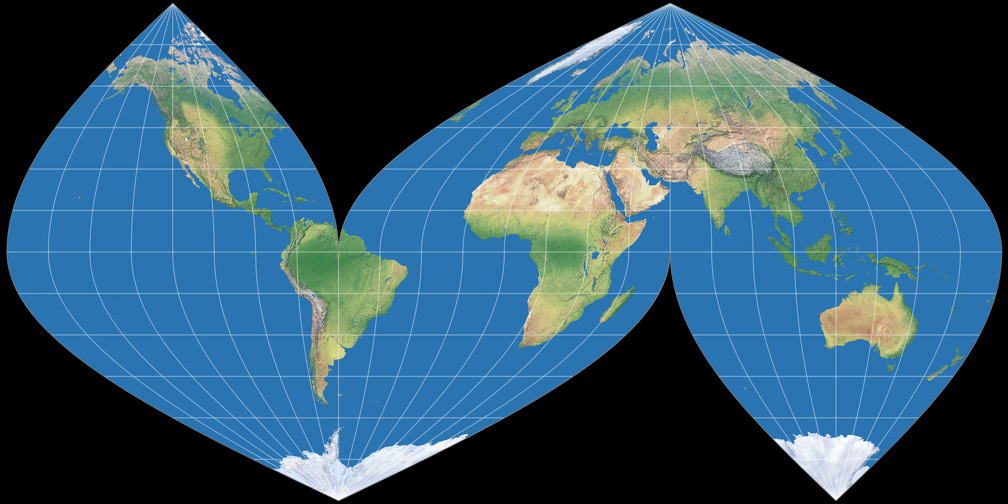

Mathematical (or simulation) modeling is not entirely useless, but it comes close. It is very useful for showing how something could work, how some set of starting conditions could lead to some outcome. It struggles to show that those conditions obtain, or what will happen when the conditions differ, or whether those initial conditions will always lead to the outcome if they do obtain. It especially struggles because the abstractions in the model do not match clearly facets of the real world. A map is a highly abstract representation of the terrain, but at least the map and terrain roughly agree on what a mile is, and what North means.

Imagine a map whose scale is internally consistent but not applicable to the Earth, and had cardinal directions wholly apart from our compass rose.

Would that map help you get where you are going, or just get you even more lost?

It is said “All models are wrong, some are useful.4” Left out is "And some models are so wrong they screw up your understanding of the world to the point you have no idea what reality looks like, and you have no desire to find out anymore because it would be too much work."

Happy trails!

Not 20 foot tall chicken’s legs, but it was really a missed opportunity.

I specify “make and sell”, because holding inventory you didn’t sell is really expensive, so if you can’t move the stuff you don’t want to make it. Average cost per unit goes up because you are making less, but goes down because you are spending less to store it all…

Nancy was amazing, and probably explained it better than I did here. She also made you feel like you should be a lot better at your job than you were, while never saying so.

Attributed to George Box, or Milton Friedman, or Fermi, depending on the discipline of the speaker, apparently.

"And some models are so wrong they screw up your understanding of the world to the point you have no idea what reality looks like, and you have no desire to find out anymore because it would be too much work."

XD

Seriously though... It seems like it should be easier to do activity based accounting with computers & spreadsheets. Unless I'm missing something....

1. "It was like a bar going BYOB but still charging you 5$ a bottle to drink it at their tables." Some restaurants call this a "corkage fee." You guys should have called yours a "cauldronage fee."

2. “Sometimes it is this way, sometimes it is that way,” - extra-stealth additional Kling reference

3. Nice article. Thanks.