Contra Kling on Price Adjustments

Sticky prices don't generally cause shortages, but persistence of shortages.

Arnold Kling again addresses questions about the cause of the recent shortage of labor, pointing to the failure of prices to adjust (wages to increase.) There is a problem with this explanation, however, and since I have brought it up over at Kling’s Substack a few times, I am going to write it up here so I can just reference it in the future.

The problem is that adjusting prices are generally the natural solution to a supply shortage, but the lack of a price adjustment is not necessarily the cause. Since price adjustments are how markets deal with shortages it is worth looking into why they are not happening, but it is also important to see why demand is now above supply such that there is a shortage to be corrected.

To head off any standard economic arguments here, I am going to start with the basics of prices and shortages, then work towards the current question. But the short version is this:

Shortages are caused by shifts in demand or supply such that quantity demanded is in excess of quantity supplied. Shortages are typically corrected by price increasing until quantity supplied and demanded are again in balance. Persistent shortages are evidence of prices not adjusting properly, but that is not the cause of the shortage, but rather the reason it is not being corrected.

Why Economists Say Shortages Can’t Persist

The market, that emergent swirl of people buying, selling, producing, consuming and causing all sorts of observable outcomes that are the result of human action but not human design, is really good at matching supply and demand. Prices go up or down as people want things more or less, or things become more or less expensive to supply, or both. Although these adjustments do not happen instantly (people need time to realize what is going on and then make the appropriate adjustments) generally prices adjust such that the quantity demanded by buyers matches the quantity supplied by sellers. This is represented in economists’ basic supply and demand graph.

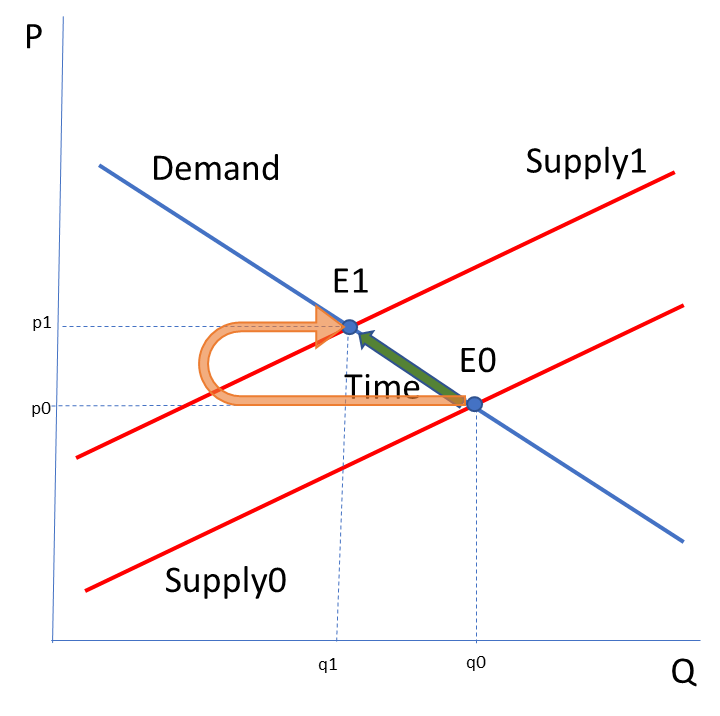

The vertical axis is Price, from zero to infinity, the horizontal Quantity over some time period from zero to infinity. Demand in blue always slopes down, as people want to buy less quantity of a good if price increases. Supply in red generally slopes up, as people want to supply more if prices increase1. Where the two lines intersect, point E0 at price p0 and quantity q0, is called equilibrium, where the price is such that the quantity demanded and the quantity supplied is the same. If nothing changes in the world, we expect prices and quantities to stay there2.

Now, the world generally changes a fair bit. People’s tastes change, maybe more people get into the market, suppliers might go out of business or new suppliers go into business, some new technology lowers production costs, and other things can change the shape and positions of the supply and demand lines. When those lines move around or change shape, that means they will intersect at a new price and quantity, a new equilibrium point, and prices and quantities will adjust over time to get to that point. Some examples:

Here we see a basic shift in supply. At time 0 the curve is one place, then something happens to make supply contract, and it shifts up and to the left by time 1. Maybe a company suppling the good goes out of business, or a plant blows up, or some necessary input gets more expensive, or a law passed increasing the cost of production, or the value of producing something else using the plant goes up so suppliers make that instead3. What happens then is price migrates upwards to p1, possibly as quantity rapidly drops to where p0 is on Supply1, then rises back to q1 as price increases. What happens in that time period depends a lot on the specifics of the particular market and how fast adjustments can happen. Just bear in mind that the adjustments are never instantaneous, and can be kind of complex, but they generally happen and a new equilibrium is reached.

So, economics text books will tell you that shortages can’t naturally exist. Particularly good economics text books will tell you that shortages can’t naturally exist for longer than it takes the market to adjust; they can’t persist, but how long they can’t persist for is a little questionable. If there isn’t enough of a good or service to go around we expect prices to increase until demand and supply intersect again, or at least until something else changes4.

Likewise, if demand increases for some reason, prices increase until enough people stop wanting the good at that price such that supply increases can keep up, i.e. price and quantity move so that demand and supply balance.

The same adjustment times and paths apply, with maybe price going up sharply until suppliers can catch up and increase quantity supplied and price comes down. How things get from E0 to E1 isn’t contained in the graph, nor how long it takes.

So, that’s why economists say shortages can’t persist: if demand outstrips supply, prices naturally go up until demand and supply are in equilibrium.

Now, this is doesn’t mean shortages can’t exist short term! Many economists make that mistake, but remember, it is the shortage that causes the prices to increase in the first place! If shortages couldn’t exist, prices wouldn’t adjust because they wouldn’t have to5. Rather, prices increasing are the solutions to shortages, just as an immune response is your body’s solution to an infection.

Say you get food poisoning from spoiled food. You now have an infection and your immune system will kick in to kill it off. If your immune response doesn’t happen that isn’t the cause of your infection, that was still eating that gas station sushi, but rather the reason you have a persistent infection.

But… Economists do talk about shortages that persist, right?

Yes, yes they do. Generally this persistence is due to a price ceiling. A price ceiling is a legal control on how high a price can be. If the equilibrium price would be above the price ceiling, you’ve got a binding price ceiling, and a serious problem.

The problem is that the amount suppliers are willing to supply at that low fixed price is much less than demanders want to buy. Thus we have a shortage. Importantly, we have a shortage that can’t be fixed by the normal method of prices increasing, so the shortage persists until people find non-price methods of allocating the goods.

Those methods are usually things like waiting in lines, bribing sellers or officials, bizarre bundling of goods6, just straight up black markets, etc. All the sorts of things people do when there is a shortage they can't deal with by nice, clean, above board monetary payments.

Where economists go wrong

Not allowing prices to adjust is just a terrible idea, probably one of the best examples of a Caplan styled “bad idea that sounds good.” Price gouging laws result in shortages all time when there is a hurricane or other natural disaster that wrecks the local economy and people desperately need ice, say. If you can’t raise the price of a bag of ice above the 2$ or whatever it was before the storm, why wouldn’t people just buy up all of it quickly, leaving nothing for anyone else? Why would anyone undergo a long, possibly dangerous trip to a nearby town to find some ice and bring back if they can only make a few bucks for their trouble? Artificially low prices are the cause of people not buying only what they need, and the cause of people not bothering to do something valuable but troublesome.

Yet… it isn’t quite right to say price gouging laws are the cause of the shortage. Imagine the towns people needed 10 bags of ice to get through the weekend, but there were only 5 to be had anywhere7… no amount of price increases are going to conjure 5 more bags of ice, and self rationing only goes so far.

More obviously, what if there had been a whole warehouse of ice bags, perhaps cleverly stored by the townsfolk after the last storm for just such an occasion, but the warehouse got destroyed by the storm, taking the ice with it. Now there isn’t enough ice because of the storm. Price adjustments might help the situation, but the shortage was caused by actual changes in supply and demand.

Remember? We said that before: shortages happen before price adjustments as a result of actual shifts in supply and demand, and the price adjustments are the market response that removes the shortage. A lack of price adjustment only causes the persistence of the shortage, not the shortage itself.

So, what causes the shortage is kind of important. Why? Because we might be causing it ourselves, or could avoid it.

Recall the example of the food poisoning. You might still be sick because your immune system is slacking off, but that doesn’t mean you should keep getting sushi at a place where you wouldn’t use the bathroom. Sure, you can’t do much about getting random colds, but actively doing something that will make you sick is just asking for you. You are causing your own infection. Stop doing that, and you won’t spend the weekend paying homage to the porcelain throne.

Likewise with markets. You can’t do much about a hurricane sweeping in and wrecking your town; nature is a mother. However, if your town council is putting limits on how much ice can be produced and stored… well that’s just stupid. That’s why you have shortages right there, hurricanes or no. Stop causing the problem, and you don’t even have to wait for prices to adjust to solve the problem, because you won’t have the damned problem.

Back to Labor and Other Shortages

That’s where I differ most with Kling, but it is a big difference. He wants to claim that labor shortages are caused by wages not increasing for some reason. Yet that is confusing the solution to the problem for the cause of the problem.

Were employers desperate for workers at the current prevailing wage rate before, say, COVID? If not, perhaps we ought to investigate why there was such a decrease in supply. If a whole lot of workers died there isn’t much to be done about that now but raise wages until enough people work to satisfy demand. If people aren’t willing to work the jobs they had before for some other reasons… well maybe we should see if we are creating those reasons.

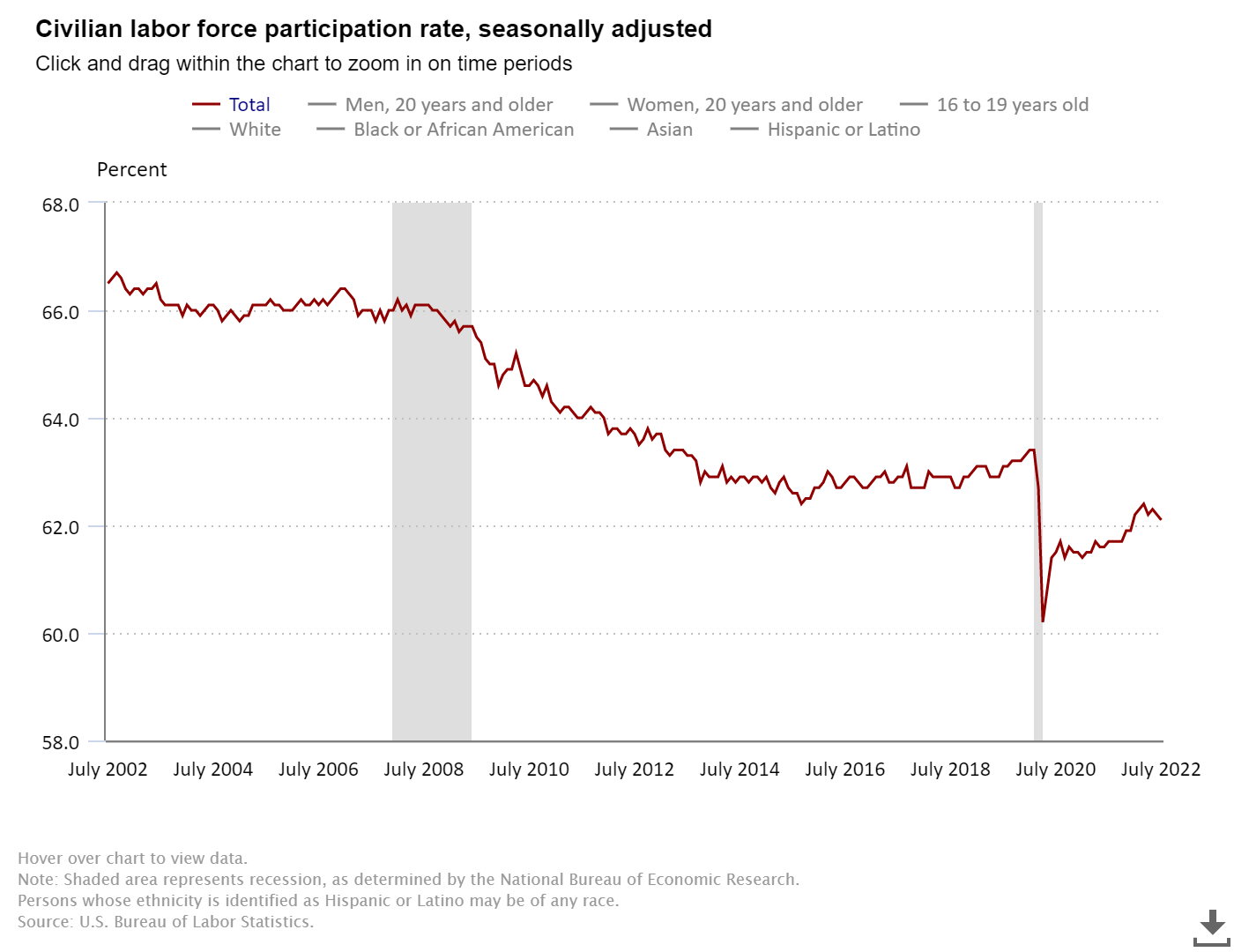

In other words, maybe we need to figure out why the percentage of eligible workers dropped down so hard the past few years:

Note that the scaling on that graph is a bit misleading: the difference between 2019 and the peak in 2021-22 is only about 1%, ~63% to ~62%. So that isn’t a huge drop, although the percentage of eligible people in the work force going dropping what looks like 4-5% from 2002 to 2022 is worrisome. What are these people doing for money? For food?

It gets a little more concerning when you see that the average hours per week worked is dropping as well, meaning many of those new jobs (and shift back into the work force) are in part time jobs, not full time.

So lots of part time workers lost their jobs during COVID, and are now getting hired back. Not great for the argument that the new jobs mean the economy is not in recession, but also note that there might be lots of people who were working part time out completely out of the work force now because the ratio is well above what it was.

What happened to all those workers that they now are deciding not to look for work?

Now, maybe it is the case that some natural occurrence is causing the shift and there is nothing we can do, or more likely stop doing, that is going to get the supply of labor back to what it was. Employers are just going to have to pay more for the same jobs than they did before COVID if they want to get enough workers.

What I think is more likely, however, is there is some policy making labor more scarce. That is, some policy that shifted the supply curve, and stopping that policy would shift it back to where it was. We could solve the shortage not by raising prices (something which might not be entirely possible if employers are quite sensitive to prices) but by ceasing to cause the shortage in the first place.

So which is it, a natural cause that we have to just suck up and deal with via higher prices, or an artificial shortage we can just end by not causing it anymore?

I don’t know for sure, but we aren’t going to find out by simply saying “If you ask a good freshman student in Economics 101 what is the cause of a shortage, you will get a quick answer, almost but not quite by rote: demand is greater than supply and for some reason, price has not risen so as to stop the shortage,” like Walter Block, as quoted by Arnold Kling8.

Find out what caused the shortage, and you will find out if it can be fixed with or without price increases. It might turn out we can just stop hurting ourselves.

The actual shapes can vary a bit, maybe being convex or concave. Supply itself often makes U shapes, as mass production allows for lower per unit costs than small batch production, but still has increasing costs overall. For general purposes here, however, we can just work with straight lines.

Note, this is the same graph whether we are talking about a single buyer or seller, or the whole market of buyers and sellers. The shapes of the curves might change, but the logic is the same in either case.

Or maybe people just forgot how to make the good cheaply, or at all. That has happened in history, usually due to population collapse. See the fall of the Roman Empire, or the story of Tasmania. Hi, Parrhesia.

If there are lots of changes bouncing around, you might find things never fully settle down to equilibrium, but always move towards it. In theory it is entirely possible that markets never perfectly clear (reach equilibrium) because changes in the market can happen faster than people in the market can react.

Or prices and quantities would adjust perfectly smoothly, implying a level of knowledge on the parts of buyers and sellers, as well as an ability to respond to that knowledge, bordering on godly. I still get business mailings for people who stopped living here over three years ago, so I think we can safely rule that out.

When I was a student at Penn State some time ago, people did a brisk business selling student football tickets. Officially you were not allowed to do this on e.g. eBay (legal price was 0$). To get around this, people would sell a pencil for 80$, and that pencil would have a protective wrapping of two student section tickets. Purely for packing and protection purposes, you understand. People bought a lot of pencils before eBay caught on.

The supply curve in this case is vertical at 5.

To be fair, Block does go on to ask why prices haven’t adjusted, but that is still down stream of why there was a shortage to be corrected in the first place.

I will use this in my microeconomics class. I have been trying to emphasise this exact point that the equilibrium point is not what is important, it is the direction of adjustment that matters. I would actually be a bit more forceful in your fourth footnote, in any large market there are always changes going on that require adjustments (some people die, some are born, some input becomes more expensive, some law changes) such that it is very hard to imagine an equilibrium ever existing for any significant amount of time.

I saw an interesting news piece that was basically a rant from an entitled woman claiming that the worker shortage was bullshit because she had applied to a bunch of jobs with no response. All I could think was that all those places were fortunate they could smell the entitlement wafting off her resume.

The thing with price adjustments is that they happen differently on the wholesale side than on the retail side as there is still more competition on the retail end. Shrinkflation is a good example on how the end user has to be tricked into accepting higher prices to reduce loss of brand loyalty.

Customers are funny on how they view price increases. I had a builder who didn't say a hint of a grumble as his door prices more than doubled in 2021 but threw a fit when I increased install price per door by $50.00.